The Day the Clubhouse Boy Pitched for Vancouver

Fifty years ago, skinny Kit Krieger went pro for a day, and achieved baseball immortality.

Krieger was the clubhouse boy for visiting teams at Capilano (now Nat Bailey) Stadium. Before taking to the field, he had laid out gum, candy, and chewing tobacco in the dressing room. He laundered and hung up the uniforms for the Hawaii Islanders players he now faced in the batter’s box, 60 feet, six inches away. Every man in Hawaii’s starting lineup had played, or would play, in the major leagues. Compared to them, Krieger was Charlie Brown. Only later would he come to appreciate how far over his head he was.

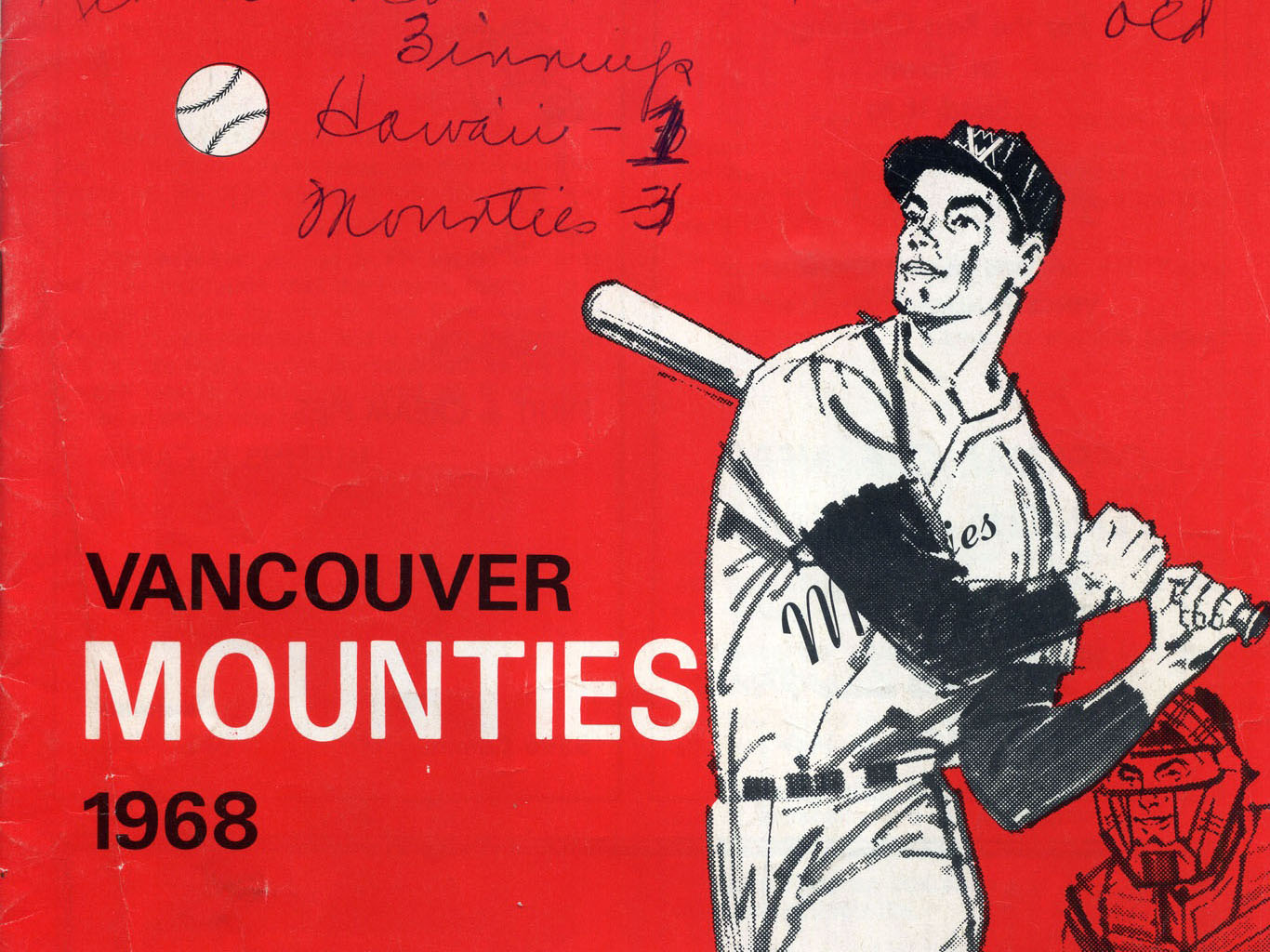

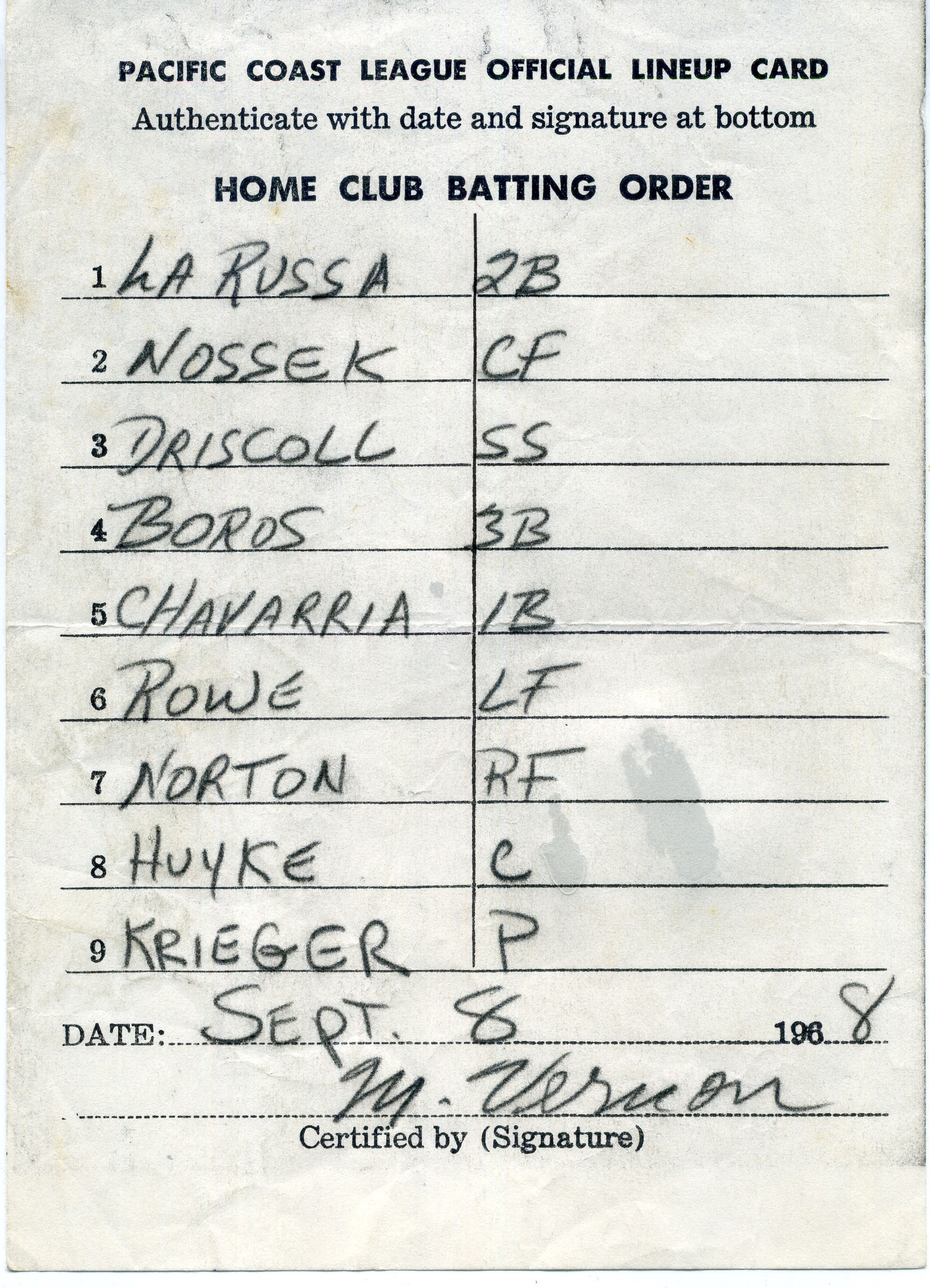

The Mounties were ending a woeful season. The team played poorly. The park was in bad shape and patrons were denied the pleasure even of enjoying a beer in the sun. Fans were scarce. On a whim, Krieger suggested to the assistant general manager he could pitch and fill the place with his friends. The assistant took it to the general manager, who then asked the manager, two-time American League batting champion Mickey Vernon, what he thought. “He’s not a prospect,” Vernon said, “but he won’t embarrass us.” It was not a ringing endorsement.

On Sept. 8, 1968, 50 years ago this weekend, the teenager stood atop the mound in borrowed cleats, wearing the uniform of a man called up to the majors earlier in the week.

The first Hawaii batter got a hit on the first pitch.

The second batter also hit a single.

They both stole a base.

A run then scored on a sacrifice fly.

The Mounties were down 1-0. Only one batter had been put out and a runner was in scoring position. Krieger now faced the cleanup hitter, Gail Hopkins, a sweet-swinging first baseman with a .338 average who had spent part of the season in the bigs with the Chicago White Sox.

Krieger had talked his way into this predicament. His mouth would not get him out of it. Like the Titanic steaming past icebergs, or the Hindenburg floating in at Lakehurst, or Ralph Branca facing Bobby Thomson in 1951, Krieger had no choice. He had to throw the ball.

‘I’ll pack the place’

Ernest Jay Krieger cannot remember a time when baseball was not part of his life. He was born in San Francisco, as was his father Edgar, who attended games at Seals Stadium, Joe DiMaggio’s first workplace. His mother, the former Ann Kohlberg, lived in an apartment building at 325 Riverside Dr. in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where the neighbour across the hall was Mel Ott, the New York Giants slugger. His parents met on a blind date during a war in which Ed would serve overseas as commander of the 663rd Quartermaster Truck Company, seeing action in the Battle of the Bulge. He met Gen. George Patton during the war and won a Bronze Star for meritorious service. The family moved to Vancouver when Kit was an infant so Ed could join his brother at Oppenheimer Brothers, a food-brokerage company older than the city (and still in operation today).

When the Giants abandoned the Polo Grounds in Manhattan to seek greater profit in San Francisco, the move united the two branches of the Krieger family tree. In that same year of 1958, Kit’s mother’s cousin, Don Taussig, a light-hitting outfielder, made his major-league debut with the Giants, sealing the family’s connection to the team. Young Kit sometimes spent summers in the Bay Area as a teenager. On July 2, 1963, the 14-year-old was about to catch the Ballpark Express for Candlestick Park when his aunt forbade him to leave as she wanted him present for a dinner party with her in-laws. He listened to as much of the game as he could on a transistor radio as Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves and Juan Marichal of the Giants pitched shutout baseball into the 16th inning, when Willie Mays ended it with a dramatic home run for a 1-0 San Francisco win. A recent book about the day was titled The Greatest Game Ever Pitched. He still resents having been forced to miss it.

After graduating from Sir Winston Churchill High in Vancouver, Krieger enrolled at Whittier College, about 30 kilometres east of Los Angeles. The liberal arts college was known for two things — the sports teams were called the Poets and the most famous alumnus was Richard Nixon, who a year later would win the presidency. An early pro-Vietnam War rally on the campus convinced Krieger he was in the wrong place. He returned to Vancouver and registered at UBC.

In the summer of 1967, he worked as an unpaid assistant to the visitors’ clubhouse manager, a classmate of his sister’s. He knew the older boy was going to be unavailable the following summer and so he hoped to inherit the job, which he did.

For a strait-laced baseball fan, the clubhouse offered an education in the wanton appetites of professional athletes. Some athletes popped greenies as though amphetamines were Smarties. As well as doing laundry, shining shoes, and chilling beer for the visiting players, Krieger was expected to let them know about the presence of Baseball Annies, women seeking to hook up. The players scouted the stands for likely partners, a practice they called “beaver shooting,” a misogynistic approach to be exposed two years later in Jim Bouton’s notorious memoir, Ball Four. Bouton pitched for the Seattle Angels in 1968 and watched on television with Krieger the chaos of that summer’s Democratic Convention.

When Krieger unpacked the bags of Bo Belinsky, a former pool hustler and unapologetic playboy, he came across a stack of love letters from women who included racy photographs. After games, he overheard players bragging about their romances with Hollywood starlets.

The money was good. The players were expected to tip about $2 per day and more if they consumed a lot of beer. With 27 players and coaches, the tips added up. He once got $25 from Billy Martin, a notorious hothead, because he let him know the Mounties catcher had a sore arm and Martin’s team could steal bases at will. Visitors tipped better when they won.

Krieger, only a few years younger than the players he served, was a popular figure. He cracked a lot of jokes. He played Bob Dylan on his guitar, singing in a deep bass. Best of all, he offered a free beer to whoever answered his daily baseball trivia question.

“Everybody liked him,” said Hawaii’s Gail Hopkins. “Skinny guy. Funny.”

On occasion, Krieger pitched batting practice, throwing from behind the safety of a screen. A left-hander, he had a heavy fastball topping out at about 84 miles per hour with a little movement, when slowed down just enough of a challenge for a batter seeking to work out a kink in a swing.

Krieger was walking along the concourse of the stadium on a beautiful summer’s day when assistant general manager Lefty Dennis bemoaned the paucity of paying customers. “Let me pitch,” Krieger said on a whim. “I’ll pack the place. I’ll sell tickets to all my friends.” Dennis told his boss Lew Matlin, who in turn ran the idea past Vernon, the field manager. They decided to let Krieger start the final game of a lost season.

Today, such a stunt would be ruined by overexposure before it had a chance to happen. Back then, the only notice was a sentence in the papers the day before.

Ten days before the game, the club gave Krieger 500 general admission tickets at $1.75 each and 1,000 special student tickets at $1 each. He put the squeeze on his friends and pestered passersby at the campus library. In the end, he sold just 46 grandstand and 159 student ducats.

Moonlight pitcher

Krieger arrived early on the morning of the game. He had duties in the clubhouse. It was a get-away date, as both teams were eager to close out the season and get on with their lives. Four of the Hawaii players had reservations for a flight out of Vancouver to New York, where they were to join the parent Chicago White Sox.

The Hawaii players knew the clubhouse boy was to pitch against them. Not all of them thought it a good idea. “This is what we do for a living,” outfielder Joe Haines told Krieger. “Like I was making a mockery of the game,” Krieger says now.

The starting pitcher for Hawaii was Bill Fischer, a month away from his 38th birthday and already a curmudgeonly figure. This was to be his last game as a player after a 21-season career that had begun with the Wisconsin Rapid White Sox in his home state. He holds to this day the major-league record for having pitched 84 1/3 innings without issuing a walk. He offered to show the rookie the ropes.

“He said to me, ‘Come out and I’ll help you get ready,’” Krieger said. The rival pitcher rolled balls to the newbie’s right and then to his left until his charge was breathing heavily. “He proceeded to give me drills to tire me out. What did I know?”

If falling for opposition hazing was embarrassing, Krieger next had to deal with his teammates. The catcher Woody Huyke went over signs with the hurler. Krieger said he had a fastball and a slider, before proudly adding he could throw a knuckleball, that unpredictable pitch that is the bane of catchers. “You break my %$#@! fingers, I’ll %$#@! kill you,” Huyke warned.

“He was,” Krieger deadpanned, “somewhat less than supportive.”

As Krieger stood on the mound, the recorded anthems played, a tinny sound echoing through the mostly empty stands. Nineteen sixty-eight was a year freighted with history — Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April, riots in Paris in May, Robert Kennedy’s assassination in June, the crushing of the Prague Spring in August. In October, two American athletes were sent home from the Olympics after delivering a black power salute from the podium. Even baseball seemed to be coming apart at the seams. Some players, including Rusty Staub, were punished by their owners for refusing to play after Kennedy’s death. Before Game 5 of the World Series, the blind Puerto Rican singer and guitarist José Feliciano played a glorious, soulful version of “The Star-Bangled Banner” for which he was booed and roundly criticized.

Krieger was not immune to the tumult. He’d been involved in the anti-war movement and would in four years become head of the local chapter of the Democrats Abroad, campaigning for George McGovern. In this moment, though, he had concerns more physical than political. In his head, he went over coaching advice about throwing the slider with the same motion used to pull down a window shade. He stared in at the catcher who threatened to kill him. No knuckleball on the first pitch. A fastball. And he needed it to be over the plate for strike.

Crack!

Angel Bravo greeted the first pitch by smacking it up the middle past the pitcher into centre field.

Jim Stewart followed by lining a single to left field.

They pulled off a successful double steal.

George Kernek lofted a fly ball just beyond Tony LaRussa at second base, which was caught by Joe Nossek in centre field. The runner on third tagged.

Here’s the thing. Nossek had pitched the previous day, going the seven-inning distance in the second game of a doubleheader. He got the win, but his arm was so sore he could barely comb his hair, let alone make a throw to the plate. The run scored.

And up came Hopkins.

And down he went.

When third baseman George Freese was retired, Krieger was out of the inning.

He walked coolly to the dugout, his head down, consciously trying to look like the ballplayers he saw in action every working day.

Krieger went scoreless over the next two innings, the only blemish another single surrendered to Stewart and a hit batter in Kernek, who took a pitch to the chest to no visible effect. “Sorry,” Krieger muttered from the mound, perhaps the first time a professional had ever apologized in that circumstance.

As Krieger entered the dugout after the third inning, Vernon said to him, “That’s it.” His place in the batting order was coming up and he would be replaced by a pinch hitter.

His pitching day done, Krieger retreated to the clubhouse to get things ready for the players after the game. He was only moonlighting as a pitcher.

Meanwhile, the game rolled past quickly. Dan O’Riley replaced Krieger on the mound. In turn, he was replaced by Ossie Chavarria, a Panamanian, who pitched an uneventful inning as part of playing all nine positions, even relieving Huyke behind the plate for a stanza.

Hawaii didn’t score again, while the Mounties scored two in the sixth when Nossek double scored Rene Lachemann and LaRussa. In the seventh, Steve Boros hit a home run, his only one of the year. O’Riley was credited with the win in a 3-1 victory, Fischer the loss, to fall to 8-9. Fischer had thrown only 71 pitches, just five more than the lowest total ever recorded in a complete game in the 65-year history of the Pacific Coast League.

The losing pitcher trudged into the visitors’ clubhouse only to find the cooler empty. “Where’s the %$#@! beer!” he demanded. Krieger’s little brother, Bob, later to be editorial cartoonist at the Province, had been so engrossed in watching his brother’s performance that he had forgotten to chill the suds. It was an ignoble end to Fischer’s long career.

The game lasted just 64 minutes.

The Islanders had agreed among themselves to swing at everything so the inconsequential game could end in time for all to make their airline reservations.

“We were all going to get out of there as fast as we could,” said Hopkins, 75, who lives in Parkersburg, W.V. As for Krieger, “we were happy he was throwing the ball close enough to the catcher so we could swing.”

Huyke, who lives in Bradenton, Fla., and who turns 81 later this month, doesn’t remember specifics of the game, but does recall being miffed at the clubhouse boy being a teammate, even for a day. “When you’re a professional,” he said, “you want to play with professionals.”

Krieger signed a pro contract for the minimum $500 per month pro-rated for one day. After he left the game, he walked into the team’s business office in his cleats. He was promptly fined a day’s pay for violating team rules.

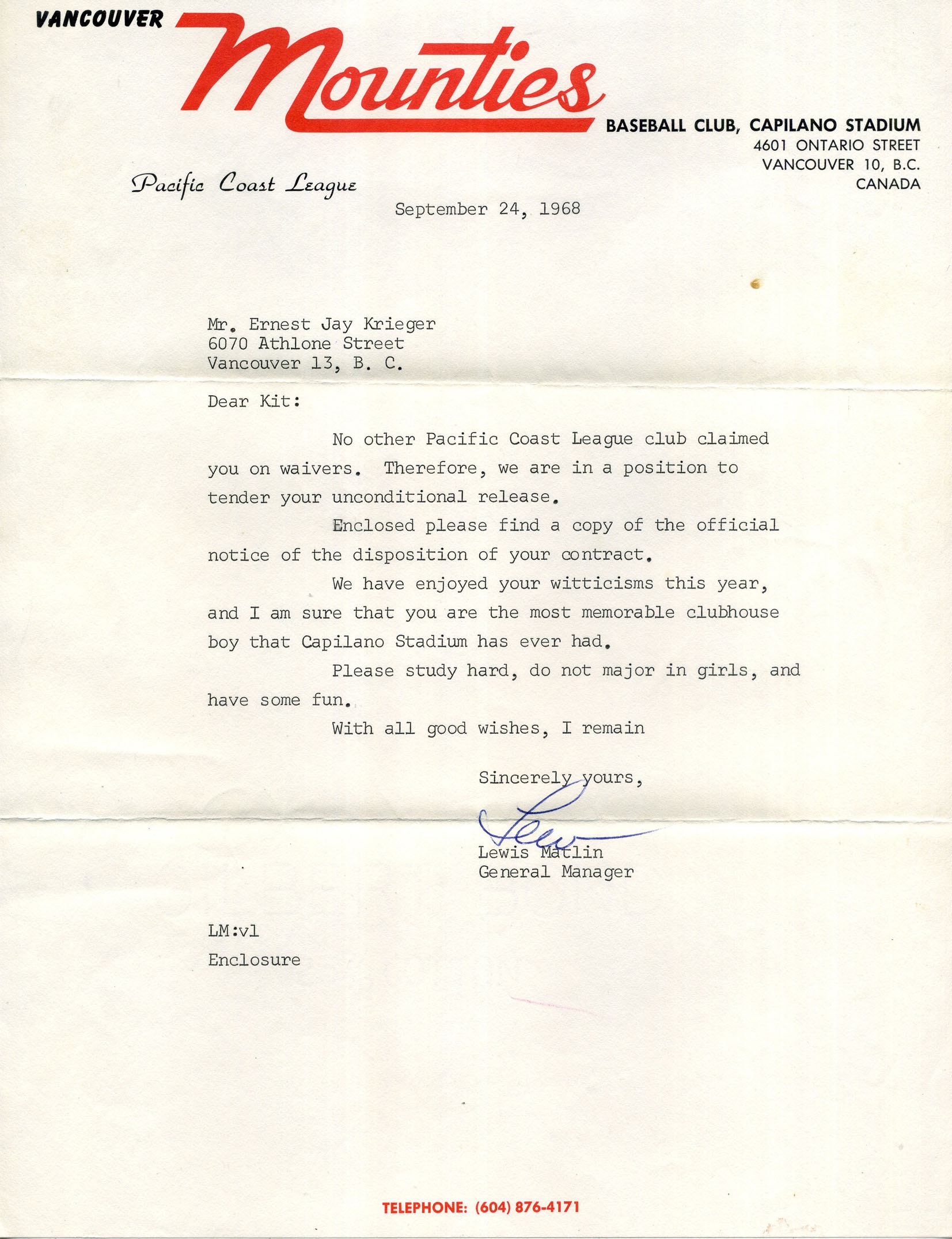

He was placed on waivers, which he cleared, after which he was given his unconditional release. The manager, Lew Matlin, sent him a letter.

“We have enjoyed your witticisms this year, and I am sure that you are the most memorable clubhouse boy that Capilano Stadium has ever had,” he wrote. “Please study hard, do not major in girls, and have some fun.”

He later got a contract from the Topps Chewing Gum seeking the rights to use his image on a baseball card should he make the major leagues. It came with a cheque for $5. He signed it and cashed the cheque.

He never played a pro game again.

A career, and lifetime highlight

Krieger kept all the ephemera from that day. He has letters, a contract, a program, the ticker tape announcing the starting batteries of pitcher and catcher. He also has a cassette of Jim Robson’s radio broadcast of the game, a highlight of which is the call of “Struck him out!” when Hopkins went down swinging. (Hopkins only struck out twice all season with Hawaii.) He also kept the two issues of The Sporting News in which his name appears.

That is the thing about baseball. If you enter a game, your name is registered and appears in baseball annuals and yearbooks and encyclopedias and now online at such sites as Baseball-Reference.com. It hints at immortality. Krieger imagines far in the future his infant grandson Max showing friends his grandfather’s entry from the mid-20th century: Krieger, three innings pitched, three hits allowed, one earned run, one strikeout, one hit batter. You can look it up.

Krieger taught high school in West Vancouver for a quarter-century before becoming president of the BC Teachers’ Federation and, later, the Registrar of the B.C. College of Teachers. He is active in Holocaust education. Those three innings stand out as the most remarkable thing he has done.

On his wedding day, he had to give a speech. He began by saying, “This is the second happiest day of my life…” (Forty-five years later, he’s still married.)

Those three innings give him entree into the world of baseball players.

“I get invited to reunions,” he said. “You’re a part of a fraternity when you play baseball. There’s a respect you get.”

He has not squandered that gift. On his first visit to Cuba on an education exchange, he indulged his passion by taking in some baseball games. He returned again and again, eventually forming a company called Cubaball to operate tours for Canadian and American fans. In his time on the island, he befriended Conrado Marrero, a star Cuban pitcher who late in his career threw for the Washington Senators. Marrero stayed after the revolution and the rest of the baseball world forgot about him. Even in Cuba some thought him long dead. Krieger cajoled letters from old American teammates and rivals, which he read to Marrero on annual visits. When he learned Marrero was not receiving a pension, Krieger lobbied for a decade to get him his money, funds that continue to support his family in Havana after his death in 2014 three days before his 103rd birthday. He continues to raise money for retired minor leaguers in Cuba. Krieger has made good use of his innings.

Lest anyone wants to sign him to another contract, he confesses he has lost some zip to his fastball. At the same time, his arm strength is good. After all, he’ll be pitching on 50 years’ rest. ![]()